The Russian - Africa summit; A Development Partnership Or An Alliance?

Click to view

FOCAC 2015, China pledges $60 billion in development funding to Africa; is this new or old money?

Click to view

European and African leaders in search of common grounds on immigration policy

Click to view

- Details

- Written by APF

- Category: Latest

- Hits: 11912

By Eric Acha

London: 14 February 2012

Image by Reuters

Image by Reuters

Somalia is once again in the spot light, this time from a rather rare, positive and an optimistic perspective. The highly anticipated London Conference on Somalia will be hosted by the British government on 23 February 2012 in London. The conference is geared at rallying the international community and increasing efforts aimed at resolving the almost two decade long conflict in Somalia.

Having been tagged repeatedly with the failed –state banner, there is some optimism within the international community to see renewed efforts geared towards resolving the challenges facing the country. Policy experts have been left baffled over the last 20 years and have failed to recommend viable policies to end the conflict that has claimed thousands of lives and rendered the country ungovernable for so many years.

It is no secret that the United Nations, the African Union and the rest of the international community’s policy towards Somalia has failed. The question on the minds of many sceptics and pessimist today is “what shall the London conference achieve?” What new theme is being discussed that has not been discussed in the past and what new viable concept is the UK going to introduce that has not yet been tried in the past.

As the world eagerly looks forward to the outcome of the London conference, the UK foreign ministry is well convinced that the conference will mark a new beginning for Somalia. In their effort to show case this optimism, senior representatives from over 40 governments and multi-lateral organisations have been invited to convene in London on February 23, with the aim of delivering a new international approach to Somalia. Top on the agenda of the half day conference will be to discuss how the international community can step-up its efforts to tackle both the root causes and effects of the problems in Somalia, and then possibly come out with a roadmap for the country.

The thematic areas to be discussed include:

1. Security: When it comes to security, Somalia has and continues to rely solely on the African Union Mission In Somalia (AMISOM). AMISOM is mandated with conducting Peace Support Operations in Somalia to stabilize the situation in the country in order to create conditions for the conducting of Humanitarian activities.

Amongst the challenges facing AMISOM, are its sources of funding. Though the foot soldiers making up AMISOM are contributed by AU member states, the mission has been reliant on external bodies and stake holders who more often than usual have conflicting interests. Besides funding, AMISOM is continuously humiliated by an insurrection of internal factions within Somalia, who regard the mission as an occupying force. The ideology being propagated by members of these resistance factions is that, so long as AMISOM continue to carry out its mission in Somalia, the country will never be able to build its own national security force that will be answerable to a legitimate Somaliland government and not to foreign forces.

This therefore explains why security will be one of the sticky and tricky issues at the London conference. The most feared faction in the country at the moment is the al-Shabab militant group.

2. Political Process: Talking of a political process, there hasn’t been any viable and a sustainable political process in Somalia for the last 20 years, whence the reason why there is no legitimate government in the country. What is currently being referred to as a political platform in the country is build on a muddy and flawed framework designed to serve the interest of factions and tribes within Somalia rather than the entire Somaliland as a nation. Critics; both scholars and policy experts have argued that the political strategy has been weaved around untenable assumptions. Abdi Ismail Samatar; a professor in Geography and one of the country’s most vocal critics has argued that one of the reasons behind Somalia’s inability to build a sustainable governments is because the international community has encouraged and supported a tribalist and clientalist political agenda in the country, a situation that led to divisions and corruption within the population.

With a parliament made up of more than half a thousand MPs for a country of that size, it becomes evidently clear that the agenda of such a parliament is not to nourish and build an able government for the country but rather aimed at sharing the national cake to the various tribes constituting Somaliland. This makes it practically impossible to genuinely debate and pass legislature governed by the democratic principle for the interest of Somalia as a nations.

This therefore implies that for Somalia to move forward and be guaranteed a governable state and a sustainable government, the London conference must agree on what should replace the current Transitional Federal Government (TFG), and that will be accepted by all Somalians. How to transform the transitional institutions in Mogadishu into structures that will ensure and foster socio-economic and political developments will be top on the topic’s agenda.

Whatever ever entity that would replace the TFG, it must be able to operate within a broad constitutional framework, and whether such an entity will be sub national or a full national government remains a question to be answered.

Local Stability: With factions fighting each one another and all with diverse and opposing opinions and agendas, maintaining stability within the Somaliland borders has proven to pose a daunting challenge to all the stake holders involved so far. Critics and sceptics of the current efforts to maintain stability within the country have argued that the international community has encouraged and continue to support a dual-track policy which exploits Somalia’s fragmented community and conflict for resource and power competition. This concept has sawn a seed of distrust into many Somalians who approach every single effort aimed at stabilizing the country with often misplaced suspicion. Most Somalians will be expecting a renewed and transparent package from the conference that will fairly encourage efforts geared toward stabilizing the country.

4. Counter Terrorism: For most part of its existence over the last 20 years or so, Somalia has been regarded as a breeding ground for terrorism on the horn of Africa. It has provided shelter and acted as a save heaven for some of the most feared terrorists around the world. The absence of an able government in the country encouraged and nourished an environment of lawlessness, where terrorist cells and networks could flourish undeterred.

5. Piracy: It is believed that Somalia has one of the most sophisticated and dangerous piracy networks in the world that has over the years transformed into a million dollar business model. Though this new gold mind industry for the pirates may be only a million dollar industry, the economic cost of their pirate activities is estimated in billions. In a recent recent paper by Anna Bowden and Shikha Basnet published by the One Earth Future Foundation, it is estimated that Somali piracy cost between $6.6 and $6.9 billion in 2011, down from a figure of $7 to $12 billion in 2010, and the shipping industry bore over 80 percent of these costs as a result of ransoms, higher insurance, security equipment and guards, re-routing of ships, increased speed and burning of more fuel, compensation of kidnapped seafarers, prosecutions and imprisonment, military operations, and the creation of anti-piracy organizations etc etc.

The international community has mobilised resources in the past to fight this crime, but with little success, giving the absence of a reliable government in the country that is capable of coordinating such efforts.

The London conference is expected to designed new strategies that will effectively combat a networked generating millions of dollars to many Somalians who have adopted piracy as a way of life. On one of the many propaganda websites managed by some factions in the country, they are of the opinion that talks on fighting piracy are ill intended, and aimed at restricting Somali territorial water and the utilization of marine resources, imposition of Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), continuation of illegal fishing and dumping toxic waste. The London conference is therefore tasked with introducing a much more robust strategy to effectively combat this crime. This may involve socio-economic alternatives for those most venerable to the flourishing piracy industry.

6. Humanitarians: What the half-day conference aims at achieving, especially on the humanitarian crisis in Somalia keeps pondering the mind of many experts, many of whom are of the view that the humanitarian crisis in Somalia require a gathering of its own, giving the magnitude and implications of the crisis. The refugee problems emanating from Somalia have spread into neighbouring countries and hence becoming a regional rather than a national issue.

Internationally displaced peoples (IDP) camps are scattered all across the country and border towns in neighbouring countries. The atmosphere in most of these camps is often that of fear and hunger. These groups of displaced Somalians are constantly frightened by the threats coming from Al-Shahab. Besides the insecurity issue, natural disasters such as drought add more stress and pressure onto these vulnerable communities, making a bad situation even worse.

Internationally displaced peoples (IDP) camps are scattered all across the country and border towns in neighbouring countries. The atmosphere in most of these camps is often that of fear and hunger. These groups of displaced Somalians are constantly frightened by the threats coming from Al-Shahab. Besides the insecurity issue, natural disasters such as drought add more stress and pressure onto these vulnerable communities, making a bad situation even worse.

Earlier this year, the UN spokes person in Mogadishu; Russell Geekie described the situation as the worse and largest humanitarian crisis in the world. Until the World Food Program stepped up their effort and increased their presence in Somalia last December, the under-funded Somali Rehabilitation and Development Agency was the sole arbiter in most of these IDP camps.

So as we all look forward to the London conference with great optimism, the reality is that the half day conference is unlikely to achieve any tangible results with regards to the humanitarian crisis in Somalia. The humanitarian crisis deserves another gathering of its own.

7. International Coordination: If one were to select a country as a lab for testing international and inter-organisational policy, Somalia would be the perfect policy lab. The country has served as a policy-testing lab for one failed policy after the other over the last 20 years. International and regional organisations have worked hand in hand alongside bilateral partners to design a sustainable and viable policy that could help end the conflict tearing the country without any success.

The United Nations, together with the African Union have champion and led such experimental policies, but as we all know today, none has been successful. There have been claims and counter claims on why no policy seem to be a viable policy for Somalia. On one hand, the international community and other partners are blamed for not addressing the root causes of the conflict while on the other hand, Somalians themselves have been accused of jeopardizing and frustrating every single endeavour aimed at stabilizing and bringing peace to the country. This therefore implies that whatever comes out of the London conference, it will be practically impossible to effectively implement any viable policy without the full and unconditional participation of the Somalians.

Ambassador David Shin, (former US ambassador to Ethiopia and Bukina Faso) recently stated that he doubts that it will be possible to end the conflict in Somalia unless the Somalis huddle to discuss their future at their expenses inside Somalia without foreign participation. The reality we know is that, left alone, Somalia is nowhere close to resolving its conflict without foreign assistance. They have continuously demonstrated over the past 20 years that they are unable to put their house in order without external assistance.

The good news is that the London conference seems to be a new dawn in the attempt to end the conflict on the Horn of Africa.

- Details

- Written by APF

- Category: Latest

- Hits: 2719

The shifting balance of complex forces of political change and governance indicates that a window for democratic breakthroughs has widened in Africa. “The continent aspires to be governed differently,” Chris Fomunyoh, working group member and Regional Director for Africa at the National Democratic Institute, told attendees. Meanwhile, the strengthening of civil society, legislatures, elections, and a range of other democratic institutions in Africa has chipped away at the monopoly on power of the executive branch. This process has also placed more pressure on Africa’s authoritarians and autocrats.

While the Arab Spring has been the focus of conversation and analysis, the report states, a momentous year for democracy south of the Sahara has gone largely unnoticed. For example, watershed elections were held in Guinea, Nigeria, Niger, Côte d’Ivoire, and Zambia. Niger and Guinea, meanwhile, reversed the corrosive effects of military coups.

While the Arab Spring has been the focus of conversation and analysis, the report states, a momentous year for democracy south of the Sahara has gone largely unnoticed. For example, watershed elections were held in Guinea, Nigeria, Niger, Côte d’Ivoire, and Zambia. Niger and Guinea, meanwhile, reversed the corrosive effects of military coups.Article link: http://africacenter.org/2011/11/catalyst-of-reform-the-arab-spring-in-africa/

Welcome remarks by Ambassador William M. Bellamy (ret.), Director of the Africa Center for Strategic Studies and comments by Joseph Siegle, Working Group Chair and ACSS Director of Research , Christopher Fomunyoh, National Democratic Institute’s Regional Director for Africa , Edward McMahon, University of Vermont Professor and Freedom House Senior Research Associate

Video link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BQmbjmVAIIA&feature=player_embedded

Article link: http://africacenter.org/2011/11/catalyst-of-reform-the-arab-spring-in-africa/

- Details

- Written by APF

- Category: Latest

- Hits: 9683

Doha Development Round: WTO talks collapse after 7 years of Negotiations

By Eric Acha

The Doha Trade Negotiation rounds first lunched in 2001 in Doha - Qatar where aimed at paying special attention to the needs and interest of the Developing Countries. The negotiations were planned to redress the perceived imbalances in the global trading system that mostly favoured the rich developed countries

The Doha Trade Negotiation rounds first lunched in 2001 in Doha - Qatar where aimed at paying special attention to the needs and interest of the Developing Countries. The negotiations were planned to redress the perceived imbalances in the global trading system that mostly favoured the rich developed countries

But unfortunately this vision and commitment seem to have kicked the bucket or to a minimum has been strangulated.

Though it may be disputed by some negotiators, it is evidently clear that the interest of the developing countries was no longer the top priorities of the negotiations as they proceeded.

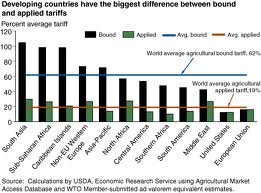

The difficulties to reach an agreement that addresses the concerns and interest of the developing countries as well as hold the potentials to raise their income and living standards, while at the same time offering sufficient incentives for the developed countries has been the major obstacle to the negotiations.As a matter of fact, agriculture and the manufacturing sector has been the point of contention and has led the negotiations a couple times to deadlock, and still are the two main issues of concern today, with agriculture being the most controversial. Before looking at where things stand today, let us take a brief retrospect over what has been going on since the first round Qatar in 2001.

Doha 2001

The Doha round which kicked off in November 2001 was actually a continuation of negotiations from the WTO ministerial conference of 1999 in Seattle (Mellinium round) which failed woefully, since some very fundamental issues had been ignored by the negotiators. It was illusory to dream of a consensus on major issues after excluding the developing countries from agricultural negotiations. This failure led to the birth of the Doha Development Agenda commonly referred to as the Doha Round.

Its agenda was broad and there was little thought on diagnosing how complicated things would be if the objectives of the Agenda had to be met. Fully opening agriculture and manufacturing markets were the main issues on the agenda as

well as trade in services and also expanding intellectual property regulations. In short it was meant to improve the current terms of trade and encourage fair trade.

With so much optimism, the negotiators were convinced things will be concluded within 4 years and hence 2006 was set as the deadline.

Cancún 2003

Two years after the lunch of the Doha rounds, trade ministers met in Cancùn to continue what they started in Doha with yet much optimism and with hopes things were getting close. Little did they know that this round was actually to unveil disparities and realities that would keep them busy and not finding consensus for the next 5 years.

It was at this ministerial meeting that the challenges posed by subsidies and full liberalization of markets really emerged in their totality. Without much wrangling, the negotiations led to a deadlock and subsequently collapsed after four days of negotiating. The sticking point here was a demand by the developing countries that the EU and the US reform their EU Common Agricultural Policy (GAP) and the US government Agro-Subsidies respectively, in order to fully scrap off the agricultural subsidies they were providing their famers. In other words, the negotiations had just begun.

Geneva 2004

A lot is considered to have been achieved during the Geneva Round of August 2004, since a framework agreements was at least achieved. The EU, USA, Japan and Brazil agreed to “reduce” (not eliminate) their export and agricultural subsidies and lower tariff barrier, while on the other hand, the developing countries agreed to “reduce” (not eliminate) tariff on manufactured goods, but at the same time gained the right to protect what they considered key industries from unfair competition.

Paris 2005

The Paris round was originally intended to round up issues discussed in Geneva and prepares a clean path for the negotiations in Hong Kong. But unfortunately issues that the negotiators thought had been vigorously discussed and concluded in Geneva resurfaced and were becoming major obstacles to any progress. French farmers through their lobbyist group protested all previous moves intended to cut farm subsidies, while the US, EU, Australia and Brazil could not agree on issues relating to chicken, beef and rice. With this, there was a feeling of pessimism since it was evidently clear that failing to find a consensus on such small but technical issues will mean harder days ahead when it comes to large political and more risky issues.

Hong Kong 2005

After 3 years of intensive negotiations and midway to the Doha rounds, the trade ministers (negotiators) finally agreed on a deadline for eliminating export subsidies on agricultural products, though without a framework to ensure its implementation. Despite lots of resistance and obstacles, the Hong Kong declaration had some substance in that, it was able to set 2013 as the deadline to eliminate those subsidies on agricultural exports with the industrialized nations opening up their markets to goods from the developing and poor countries.

Geneva 2006

The sticking issue at this meeting in Geneva was the farming subsidies that had been a point of contention during the Paris meeting. The negotiators failed to agree on the demand to reduce farming subsidies and lowering import taxes. It posed so much threat to the entire negotiations so much that, some sceptics where concluding the Doha-Development Agenda was going to collapse. Many thought since the US trade Act of 2002 granted to the President of the United States G.W. Bush was due to expire in 2007, any subsequent Trade deal will need to be approved by the US congress with the possibilities of amendments, an issue which will be at odds with most of the negotiators. This fact alone demotivated most negotiators. The round is some how believed to have been saved by Hong Kong, that acted as a mediator to the collapsed trade liberalization talks.

Potsdam 2007

What actually transpired in Potsdam in 2007 that led to a deadlock is still being disputed by many today. But the truth is that, the discrepancies were nothing new to the negotiators and they all understood that nothing good was going to come out of the conference, since the US, EU, Brazil and India were still unable to find common grounds on a range of issue. What I will term the “old disagreement” which was, and still is, and will continue to be is the call for the full liberalization of the agricultural and industrial market and also the total cancelation of farm subsidies by the US and the EU. These are the sticking issues that led to the break down of the conference. However, the trade ministers left Potsdam with optimism following some consolatory notes from Pascal Lammy, the Derictor General for the World Trade Organization (WTO), hoping things will be easier when the talks resume on July 21st 2008 in Geneva. How I wish they all knew what awaited them.

Geneva 2008

Prior to the kick off the conference on July 21st, there was so much optimism that the negotiations were nearing conclusion and could get done before the year runs out. Even the Director General of WTO showed same optimism on many occasions, despite knowing the complexity. During his intervention at the International Monetary and Financial Committee meeting on 12 April 2008 in Washington, he urged financial leaders to push “now” for the conclusion of the Doha Round. Hear him:

“Last year I told you about the risks of a failure in the Doha Round. A sort of half empty glass. This year I am completely convinced that we have it within our means, politically and technically, to finish the Doha Round this year. To do so, the first step we need is for WTO Member governments to agree at Ministerial level by the end of May on the framework for cutting agricultural tariffs, agricultural subsidies and industrial tariffs.”

Looking closely at how the talks ended in Potsdam in 2007, it will beat the imagination of any good thinking human being why there was so much optimism. I am an optimist but as long as these talks were concern, but I could look straight into any face and say without stuttering that the negotiations will go beyond 2008 if actually the differences needed to be sorted out and the Doha development round Agenda maintained.

The issues at stake are so technical and politically complicated so much that finding a win-win compromise will require many political and economic sacrifices from all parties. But this willingness was lacking despites the fact that the conference took off on a positive node in Geneva.

Even though taking off on a good foot, the negotiations where in a deadlock for four days until a consensus was reached on the extent of farm subsidies reduction within the EU and the US. It was agreed that the EU will cut its farm subsidies by 80% while the US will do same by 70%. France and Italy reluctantly bowed to this proposal but with lots of reservations. The percentages sound really much but the fact is, in reality it is not enough to avoid the distortion these farm subsidies are causing to world prices and the havoc it brings to millions of poor farmers in the developing countries.

On the other hand, it was not possible to fully convince India, China and Brazil to fully accept the terms of opening up their markets to industrial goods from the developed countries. China and India are being accused for being behind the current deadlock.

The nature of these negotiations is so complex that even the developing countries that ought to be speaking with one voice are more often divided than united when their interest is at stake. This was once again proven on Sunday 27th, when the Latin American countries and the EU came out celebrating after settling their long standing dispute over EU imports of Bananas. Until this day the deal had favoured only former European colonies in the African, Caribbean and Pacific (the so called ACP countries) that were exempted from import tariffs on Banana. The ACP cried foul at this move and threaten a total blockade of the negotiations if the agreement was not reversed and overhauled. The fact is, the deal had been stroked and the cries were falling on deaf ears.

The EU had once more outsmarted the ACP member states with this move and at this point, good thinking minds should start questioning the true intensions of the bilateral Economic partnership Agreement the EU signed with most of these ACP member states. One can now have an understanding of why there was so much pressure exerted on the ACP member states by the EU negotiators to sign the Economic partnership Agreement (EPA) at the beginning of this year.

I will attempt making some analysis in my next post on the technical reasons delineating why the Doha Agenda is practical impossible, though if attained will end a lot of mass suffering in most developing countries. But until then, the DOHA ROUND IS DOOMED!

- Details

- Written by APF

- Category: Latest

- Hits: 14972

The security challenges facing Africa are enormous and multifaceted. These challenges are both conventional and non conventional, e.g violent extremism, insurgency, armed robbery, piracy, narcotic trafficking, human trafficking, post-conflict stabilization, resource, identity conflict and other forms of organised crime. Terrorism is also on the rise in some regions of the continent.

Given this wide array of challenges, coupled with the high level of unemployed youth and bad governance across most of the continent, there are growing concerns of a long term deteriorating effect.

On one hand proponents of democracy have argued that good governance is the key solution to this problem while on the other hand, development experts see the problem through a different prism. They argue that under development and the lack of opportunities for a better life are the driving factors behind much of the insecurity on the continent. The struggle over scarce and natural resources has been identified as the core of the major conflicts in Africa.

Oil, Gold, Diamond, Bauxite, Timber and even water are some of the many resources that have recently pushed countries and communities across Africa into costly wars. The rise of piracy in the Somalia waters has opened a new front that needs urgent attention.

Both regional and international partners are engaged in a fierce battle to curb and mitigate as well as prevent all these security concerns. The rise of political instability as a result of bad governance as well as bad diplomacy by the international community in some cases is exacerbating pressure on these efforts.

How the continent will fairy and overcome these security challenges over the next years is an issue occupying the minds of most Africa security experts.

Making Africa safe is fast becoming a priority to many external partners given the strategic importance of the continent as the world economic dynamics continue to evolve with the compass pointing toward the continent.

It is in this light that the Africa Policy Forum has made security one of its core are areas of interest. We shall be engaging our experts and partners in this field for insightful debates, as well as making available selected publications on the issue for our audience.

- Details

- Written by Eric Acha

- Category: Latest

- Hits: 7768

Where the Doha Development Round stands, and what is holding it?

By Eric Acha

This post is a recap of a mail I sent to a friend a few days ago, on answering his question on what are the sticking points to the Doha Development round. However, I have covered the issue more extensively than in my previous response.

This post is a recap of a mail I sent to a friend a few days ago, on answering his question on what are the sticking points to the Doha Development round. However, I have covered the issue more extensively than in my previous response.

As the title of the blog delineates, I have decided to look at where things are at the moment and where the round could be heading to. More importantly is my fair criticism to what Professor Robert E. Baldwin recently put forward as an ultimate solution to the current sticky issue on the additional agricultural safeguard measures holding the DR negotiations. It takes much courage to dispute the views of such a senior scholar, but being an economist, he will take no offence for he knows the discipline is what it is, thanks to the fact that your thoughts are open for criticism as long as a valid one can be found.

For those not familiar with the negotiations, since the first phase in Quarter, each round starting from Doha through Cacün, Paris, Geneva, Hongkong, Geneva, Potsdam, Geneva have had its sticky point that led to a deadlock or a suspension of the session.

However, the early phase of DR negotiations was marred with disagreements on the scale of agricultural subsidies elimination and the liberalisation of the manufacturing sector in the developing countries.

The sticking point here was a demand by the developing countries that the EU and the US in particular, should reform their EU Common Agricultural Policy (GAP) and the US government Agro-Subsidies respectively, in order to fully scrap off the agricultural subsidies they were providing their farmers.

On the other hand, the US was demanding more access (liberalisation) of the manufacturing markets in these developing countries, an issue which was of big concern to the emerging markets especially India, Mexico, Brazil and China.

On a face value, the demands from the both sides might sound quite simple, however, the duration and difficulties on reaching an agreement speaks for itself and makes clear how complicated the whole negotiations are. It has kept the smartest economists and trade experts busy for about a decade today and models have been build to explain the gains and loses that will be involved when a complete agreement is finally reached under the current Doha Round agenda.

Some economists have question if the anticipated gains from DR (in welfare terms) are worth all these negotiations and resource squandering. This thus, has led to the claim that the mercantilist approach of most negotiators involved should shoulder part of the blame.

Going back to the issue, when a deal and compromise was finally brokered on how the US and EU should eliminate their subsidies, many thought the DR would be finalised without much technical difficulties, given that proposals were also made on how the developing countries would liberalise their markets without putting their home industries at risk.

Under the WTO work program, the Doha Ministerial Declaration commits WTO members to providing special and differential treatment with regards to agricultural products for developing countries. This obligation does however, fall short of detailing a special agricultural safeguard measure for these countries.

It was based on this lapse that the developing countries, under the auspices of India requested at the start of the negotiations in 2001 that additional agricultural Safeguard measures be introduced to protect the farmers in these countries in the event of a surge in imports from the developing countries or a decline in world prices that could put the livelihood of their home farmers at risk.

As opposed to the standard safeguard provisions of the GATT/WTO (that require proof of injury or threat of injury before tariffs can be imposed), the requested agricultural safeguard measures will allow the developing countries to raise tariffs in case of such a threat (without due procedure)

The measures were introduced and this seem to have been the stumbling block that led India and US into a confrontation at the last meeting in July 2008.

This may be, explains why India and the US are thought by many to have been the reason behind the last deadlock.

There was no major objection to the overall idea of increasing tariffs, and hence at the Hong Kong ministerial conference in December 2005 WTO members formally agreed that such a special safeguard mechanism covering both quantity and price triggers should be part of the final deal. But the technical difficulties that led to a deadlock was when, by how much and for how long should such special tariffs be in place.

What would be the volume of product inflow that will justify a tariff increase?

So as you can see, what is holding the DR is merely a technical issue, but that seem more complicated than many including the negotiators are taking it to be. It could require just some simple arithmetic but the economic implications and interpretations has magnified the issue and turn to pose more stumbling blocks as it seem to be the case now, and truly, in trade agreements (as Professor Baldwin put it) the devil is in the detail, and yet the problem with his proposal is sort of another devil in the details.

As I pointed out in the last post the stalemate is centred on three issues which are :

- The amount imports must increase before additional protection would be permitted;

- The amount tariffs could be increased; and

- How long they could be maintained.

The current rejected proposal by the WTO Director General Pascal Lamy, which also answered the question on whether the tariff increases could exceed pre-Doha Round rates. He proposed that developing countries be allowed to raise tariffs by up to 15% if the increase in imports of an agricultural product over a three-year moving average exceeded 40%. He also proposed pre-Doha round rates could be exceeded on no more than 2.5% of a country’s tariff lines, and aspect India, China and a host of other countries vehemently rejected on grounds that it will hinder their ability to prevent their local farmers in the event of an import surge, and as a result counter -proposed that: the permitted tariff increase could rise to 30% over pre-Doha Round bound rates on up to 7% of tariff lines.

The major flaw with the current proposal as Prof. Baldwin points out, is the inability of the current rigger mechanism to distinguish between import surges that do not threaten the livelihood conditions of developing country farmers and those that do.

Agricultural safeguard measure triggers under the Doha Round as opposed to the those under the Uruguay Round (based on market access opportunities defined as imports as a percentage of the corresponding domestic consumption) are expressed simply as percentage increases in the volume of imports over the preceding three years or percentage decreases in a product’s import price compared to its monthly average over the preceding three years.

Using some arithmetic, Baldwin argues that, the effect of a given percentage increase in the volume of imports on the livelihood conditions of domestic farmers varies greatly depending on the level of import penetration. For example, he points out that if the initial import penetration ratio is 5%, a 20% increase in imports means the domestic supply of the product doesn’t change much. This imply that the supply on the domestic market only by 1%, and thus will have no effect on the food security concerns that may guarantee protectionist response. But if the initial import penetration were 50%, a 20% increase in imports would mean a 10% increase in the product’s and thus a credible threat to the local farmers likelihood and hence a justification for protectionism. As Baldwin points out the proposed mechanism failed to distinguish between such obviously different cases and hence a source for conflict.

What he proposes as a better mechanism will be that which distinguishes between when developing countries do and do not need additional import protection to maintain food security and livelihood conditions of their poor farmers, and should be simply the percentage increase in imports divided by the average consumption of the product over a recent period. Many any historical effects of increases in developing country agricultural imports that will warrant protectionism should be calculated as a percentage of the domestic consumption of that particular product.

Now this is where I find a problem with the reasoning and implications behind this proposal. Though the technical calculation is accurate, the reasoning is some what flawed. Specifying safeguards based on this imply that triggers will be specified based on the consumption ratio of the particular product observed over the preceding three years. The proposal does not accommodate the possibility of a surge in an unobserved but closely related substitute. The surge in such a substitute could certainly divert consumption from the observed and the to-be protected product.

For example, if there are major concerns that the local farmers likelihood will be at risk, if there is a surge in the importation of grains (e.g rice) that is also exported and consumed locally then certainly the consumption and trade in rice will be observed very closely, without much attention paid to other grains. Not monitoring Wheat that is not grown locally and that can act as a perfect substitute for rice could lead to the same adverse effects on the livelihood of the local farmers if there is a surge in the importations of wheat.

Under the current safeguard measures and Baldwin proposal such substitutes are not taken into consideration, and even if these where to be included in the proposal, the next problem I already foresee will be the definition of the substitutes and what will constitute such substitutes. My reasoning may be wrong as well, so I will very much welcome any constructive criticism or corrections.

It was rumoured before the G20 summit in London last week that some compromise had been reached and that talks [between India/US] will continue at the summit, and may be finalised. This was wishful thinking, firstly because as long as there is yet no optimal solution to this stalemate, one can’t see the Doha round ending any time soon and secondly it would have been naive to think that the London summit will abruptly finalise negotiations that have been on going for close to a decade now just because Obama has been elected president.

Again the new Obama administration needs time to familiarise itself with the negotiations even if the negotiators are still the same, and as we all saw, nothing more could be expected than the promise to fully recommit itself to the negotiations and see them finalised as soon as possible. Many critics think this was a somewhat vague statement given that no date line was set by the world leaders if really there wanted to see the negotiations finalised.

But any honest economist will tell you the Doha round is far from over if the key negotiators are not willing to make sacrifices and disease from their mercantilist practices.

The Russian - Africa summit: A Development Partnership Or An Alliance?

Amidst the ongoing war between Russia and Ukraine, Russia has somewhat succeeded in organizing a second Russia-Africa summit in St [ ... ]

News+ Full StoryThe New International Financial System?: 10 Recommendations On What Africa should Should Do

June 20th, 2023

To be better placed to benefit from any new Financial system, there is a list of house-keeping [ ... ]

News+ Full Story

The Cost of Saving the Climate On Africa

African countries, though at the bottom of the scale of polluters, are under enormous pressure to commit to low carbon emission development models, in line with [ ... ]

News+ Full Story

Dr. Ngozi Okonjo

Biography of Ngozi Okonjo-IwealaDr Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala is a global finance expert, an economist and international development professional with over 30 years of experience working [ ... ]

Featured Leaders+ Full Story